How War in Ukraine Is Increasing Inflationary Pressure Across World’s Regions

Alfred Kammer is the Director of the European Department at the International Monetary Fund (IMF); Jihad Azour is the Director of the Middle East and Central Asia Department at the IMF; Abebe Aemro Selassie is the Director of the African Department at the IMF; Ilan Goldfajn was Governor of the Banco Central do Brasil (BCB) from May 2016 until February 2019; Changyong Rhee is the Director of the Asia and Pacific Department at the IMF.____

Beyond the suffering and humanitarian crisis from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the entire global economy will feel the effects of slower growth and faster inflation.

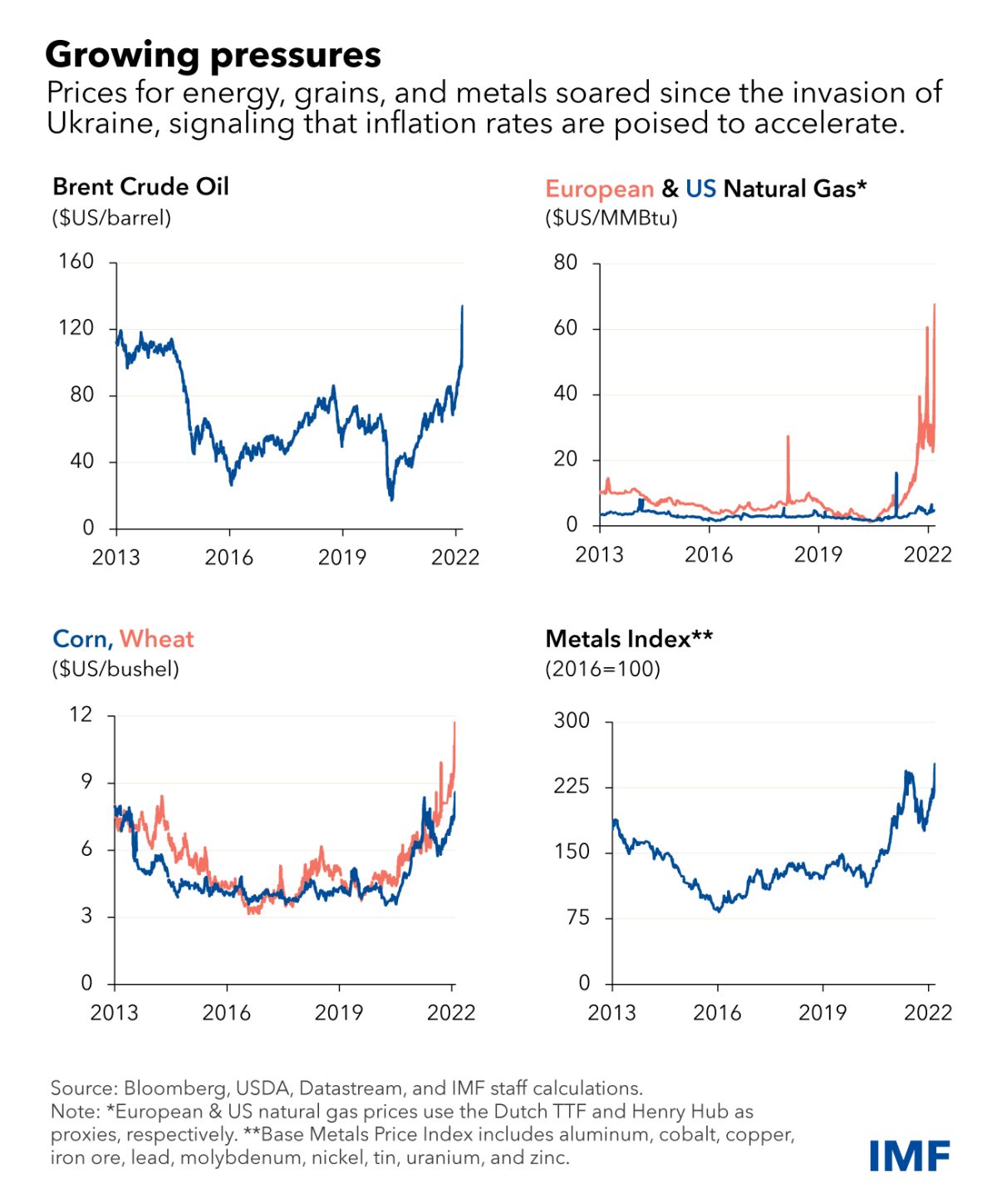

Impacts will flow through three main channels. One, higher prices for commodities like food and energy will push up inflation further, in turn eroding the value of incomes and weighing on demand. Two, neighboring economies in particular will grapple with disrupted trade, supply chains, and remittances as well as an historic surge in refugee flows. And three, reduced business confidence and higher investor uncertainty will weigh on asset prices, tightening financial conditions and potentially spurring capital outflows from emerging markets.

Russia and Ukraine are major commodities producers, and disruptions have caused global prices to soar, especially for oil and natural gas. Food costs have jumped, with wheat, for which Ukraine and Russia make up 30% of global exports, reaching a record.

Beyond global spillovers, countries with direct trade, tourism, and financial exposures will feel additional pressures. Economies reliant on oil imports will see wider fiscal and trade deficits and more inflation pressure, though some exporters such as those in the Middle East and Africa may benefit from higher prices.

Steeper price increases for food and fuel may spur a greater risk of unrest in some regions, from Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America to the Caucasus and Central Asia, while food insecurity is likely to further increase in parts of Africa and the Middle East.

Gauging these reverberations is hard, but we already see our growth forecasts as likely to be revised down next month when we will offer a fuller picture in our World Economic Outlook and regional assessments.

Longer term, the war may fundamentally alter the global economic and geopolitical order should energy trade shift, supply chains reconfigure, payment networks fragment, and countries rethink reserve currency holdings. Increased geopolitical tension further raises risks of economic fragmentation, especially for trade and technology.

Europe

The toll is already immense in Ukraine. Unprecedented sanctions on Russia will impair financial intermediation and trade, inevitably causing a deep recession there. The ruble’s depreciation is fueling inflation, further diminishing living standards for the population.

Energy is the main spillover channel for Europe as Russia is a critical source of natural gas imports. Wider supply-chain disruptions may also be consequential. These effects will fuel inflation and slow the recovery from the pandemic. Eastern Europe will see rising financing costs and a refugee surge. It has absorbed most of the 3 million people who recently fled Ukraine, per the United Nations.

European governments also may confront fiscal pressures from additional spending on energy security and defense budgets.

While foreign exposures to plunging Russian assets are modest by global standards, pressures on emerging markets may grow should investors seek safer havens. Similarly, most European banks have modest and manageable direct exposures to Russia.

Caucasus and Central Asia

Beyond Europe, these neighboring nations will feel greater consequences from Russia’s recession and the sanctions. Close trade and payment-system links will curb trade, remittances, investment, and tourism, adversely affecting economic growth, inflation, and external and fiscal accounts.

While commodity exporters should benefit from higher international prices, they face the risk of reduced energy exports if sanctions extend to pipelines through Russia.

Middle East and North Africa

Major ripple effects from higher food and energy prices and tighter global financial conditions are likely. Egypt, for example, imports about 80% of its wheat from Russia and Ukraine. And, as a popular tourist destination for both, it will also see visitor spending shrink.

Policies to contain inflation, such as raising government subsidies, could pressure already weak fiscal accounts. In addition, worsening external financing conditions may spur capital outflows and add to growth headwinds for countries with elevated debt levels and large financing needs.

Rising prices may raise social tensions in some countries, such as those with weak social safety nets, few job opportunities, limited fiscal space, and unpopular governments.

Sub-Saharan Africa

Just as the continent was gradually recovering from the pandemic, this crisis threatens that progress. Many countries in the region are particularly vulnerable to the war’s effects, specifically because of higher energy and food prices, reduced tourism, and potential difficulty accessing international capital markets.

The conflict comes when most countries have minimal policy space to counter the effects of the shock. This is likely to intensify socio-economic pressures, public debt vulnerability, and scarring from the pandemic that was already confronting millions of households and businesses.

Record wheat prices are particularly concerning for a region that imports around 85% of its supplies, one-third of which comes from Russia or Ukraine.

Western Hemisphere

Food and energy prices are the main channel for spillovers, which will be substantial in some cases. High commodity prices are likely to significantly quicken inflation for Latin America and the Caribbean, which already faces an 8% average annual rate across five of the largest economies: Brazil, Mexico, Chile, Colombia, and Peru. Central banks may have to further defend inflation-fighting credibility.

Growth effects of costly commodities vary. Higher oil prices hurt Central American and Caribbean importers, while exporters of oil, copper, iron ore, corn, wheat, and metals can charge more for their products and mitigate the impact on growth.

Financial conditions remain relatively favorable, but intensifying conflict may cause global financial distress that, with tighter domestic monetary policy, will weigh on growth.

The United States has few ties to Ukraine and Russia, diluting direct effects, but inflation was already at a four-decade high before the war boosted commodity prices. That means prices may keep rising as the Federal Reserve starts raising interest rates.

Asia and the Pacific

Spillovers from Russia are likely limited given the lack of close economic ties, but slower growth in Europe and the global economy will take a heavy toll on major exporters.

The biggest effects on current accounts will be in the petroleum importers of ASEAN economies, India, and frontier economies including some Pacific Islands. This could be amplified by declining tourism for nations reliant on Russian visits.

For China, immediate effects should be smaller because fiscal stimulus will support this year’s 5.5% growth goal and Russia buys a relatively small amount of its exports. Still, commodity prices and weakening demand in big export markets add to challenges.

Spillovers are similar for Japan and Korea, where new oil subsidies may ease impacts. Higher energy prices will raise India’s inflation, already at the top of the central bank’s target range.

Asia’s food-price pressures should be eased by local production and more reliance on rice than wheat. Costly food and energy imports will boost consumer prices, though subsidies and price caps for fuel, food, and fertilizer may ease the immediate impact—but with fiscal costs.

Global Shocks

The consequences of Russia’s war on Ukraine have already shaken not just those nations but also the region and the world, and point to the importance of a global safety net and regional arrangements in place to buffer economies.

“We live in a more shock-prone world,” IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva recently told reporters at a briefing in Washington. “And we need the strength of the collective to deal with shocks to come.”

While some effects may not fully come into focus for many years, there are already clear signs that the war and resulting jump in costs for essential commodities will make it harder for policymakers in some countries to strike the delicate balance between containing inflation and supporting the economic recovery from the pandemic.

___

This article first appeared on blogs.imf.org.____Learn more:- Fed Can’t Stop Prices From Going Up Anytime Soon, But There’s Good News, Too- Ukraine War Raises Questions About the ‘End of Monetary Regime’ and Role of Bitcoin

– Bitcoin, the Ukraine Crisis and the Central Bankers Dilemma- Could the Ukraine Invasion Spark a Global Financial Crisis?- As Inflation Is Here to Stay, Bitcoin, Ethereum, and Gold Investors Will Win, But Brace for Volatility – BitMEX

– Bitcoin in an Interest Rate Rising Environment- How Raising Interest Rates Curbs Inflation – and What Could Possibly Go Wrong